1963 March on Washington: History, Speech, Significance, & Other Interesting Facts

March on Washington (1963): History, Significance, Key Speakers, Famous Speeches, & Other Interesting Facts

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took place on August 28, 1963 in our nation’s capital, Washington, D.C. The protest was in response to decades of painful racial discrimination and segregation against African Americans in the United States. Its main goal was to secure for black Americans and other ethnic minorities equitable economic opportunities and civil rights. It also highlighted the challenges that African Americans still faced 100 years after the abolishment of slavery.

Organized by renowned civil rights activists A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, the event garnered support from other civil rights groups and religious bodies. It’s estimated that over two hundred and fifty thousand participants attended the march, including people of various ethnicities, making it one of the biggest political marches in the history of the United States.

The March on Washington was where civil rights advocate Martin Luther King Jr, gave his world famous “I Have a Dream” speech, which in turn injected a great deal of momentum into the fight for change and equality in America.

Below, World History Edu explores the major events that led to this famous march in our nation’s history. The article also looks at the role Dr. King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) played in the protest march on the nation’s capital.

Lives of Black Americans after slavery got abolished in the 1860s

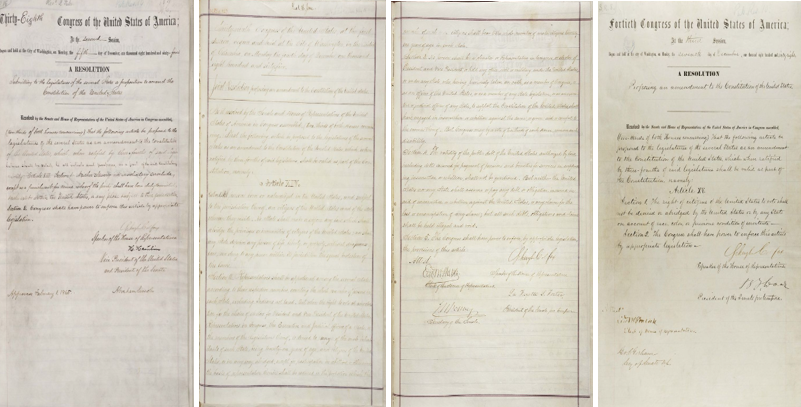

On December 6, 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ratified by the required 27 of the then 36 states of the United States. The 13th Amendment abolished all forms of slavery, except as punishment for a crime. Considered the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments, the 13th Amendment was passed by the US Senate and the House of Representatives on April 8, 1864 and January 31, 1865, respectively. It seemed like a promising time for African Americans, as they hoped that they would be integrated into mainstream society and enjoy several rights that they never had.

Three years after the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified, a second Reconstruction Amendment, the Fourteenth Amendment, was ratified. This constitutional amendment gave all African Americans the right to become citizens of the United States. In February 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment gave African American men the right to exercise their franchise.

The Reconstruction Amendments were adopted in the aftermath of the American Civil War (1861-1865), a bloody four-year war which pitted the Union (Northern states) against the Confederacy (Southern states). The war happened after years of tensions between the Northern and Southern states on issues such as the economy, culture, and the federal government’s control over the states. Undoubtedly, the biggest trigger of the war was slavery. By the mid-19th century, several Northern states had legally abolished slavery, especially as the main source of generating income had shifted from agriculture to industry. But in the South, which still depended heavily on agriculture to drive its economy, still needed slaves to work on various plantations and farms.

Following the bloody four-year Civil War (1861-1865), Congress passed three Reconstruction Amendments (i.e. the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution) that placed freed slaves on an equal footing as whites in terms of civil rights. As part of the requirement for their readmission to the Union, former Confederate states were required to ratify those amendments.

Ultimately, the Union won the war, and the United States entered the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877), where the country tried to readmit ex-Confederate states (i.e. the South) to the Union. It was also during that period that freed slaves (freedmen) and Black Americans were given more rights in a bid to reduce racial discrimination.

In spite of the ratification of those very noble Reconstruction Amendments, there were some notable Southern politicians and groups, including the white “Redeemers” and the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), that continued to oppose full rights and suffrage for freedmen. Those white supremacist groups fought tooth and nail against the racial progress that were being made during the Reconstruction Era. They employed many barbaric tactics, including lynching and murder, so as to intimidate freedmen in those former Confederate states. Image: A Bureau agent stands between a group of whites and a group of freedmen. Harper’s Weekly, July 25, 1868.

In reality, the institutions that were meant to enforce those laws failed miserably. Therefore, legal equality for black people remained mirage for many, many decades until the Civil Rights Movement was galvanized in the 1950s and 1960s. More on this below.

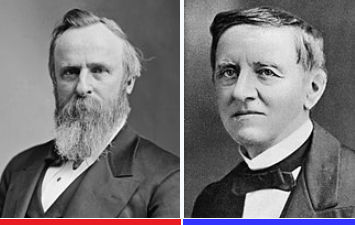

But the Reconstruction Era ended in 1877 following the Compromise of 1877 agreement between the Democrats and Republicans. During the November 1876 elections, Samuel J. Tilden and Rutherford B. Hayes contested under the Democrat and Republican parties, respectively.

Initially, the Democrats were in the lead (electoral and popular votes), however, the Republicans refused to accept their impending defeat and accused the Democrats of using fear and violence to intimidate the newly enfranchised African American voters from voting in three Southern states – Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida. Those three states were the only ones that still had Republican governments and their results went in favor of Hayes, thus giving him the needed electoral votes to win the election.

To avoid any attempts at another secession, the US Congress intervened to declare Hayes the winner. Prior to that, some Southern Democrats and Congressional Republicans met behind the scenes in hopes that Hayes would be confirmed president on the condition that federal troops would be withdrawn from those three Southern states. It was also agreed that there would be zero interference from federal government when it came to race relations in the Southern states.

The Compromise of 1877 was a deal struck between the Republicans and the Democrats to resolve the disputes that arose from the 1876 presidential election. There were many allegations of violence and disfranchisement of Republican Black voters, especially those in former Confederate states. The biggest bone of contention were the 20 electoral votes that Democrat Tilden claimed to have won in four states – South Carolina, Louisiana, Oregon, Florida. In the end, the 20 contested electoral votes were conceded by the Democrats to the Republican nominee Hayes. However, the concession came with a condition: Congress would roll back on the hard-fought efforts to end racial discrimination, segregation, and violence in the South. As a result the Reconstruction Era came to an end, as the last remaining federal troops were pulled out from those former Confederate states. Image (L-R): Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel J. Tilden

With the agreement in place, the Southern states could now impose racist laws (i.e. Jim Crow laws) against African Americans. By the early 1900s, both African Americans and poor whites had their rights to vote restricted or stripped off them.

And by the early 1950s and 1960s, the entire South seemed to be on a tipping point as segregation and racial discrimination were further fueled by the strengthening of Jim Crow laws. Several Black Americans were violently prevented from exercising their rights. In some states, interracial marriages were illegal as racial violence became the order of the day.

Read More: 10 Major Accomplishments of Rutherford B. Hayes

Did you know…?

- It’s worth mentioning that Congress even offered some bit of reparations to former slaveowners but failed to give any to former slaves.

- Fearing another outbreak of secession or worse a civil war, Congress during the Reconstruction Era were a bit reluctant to provide full protection to African Americans, especially Union soldiers, that were constantly terrorized and murdered by violent groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). For decades, African Americans wallowed in deep poverty, diseases and unimaginable suffering as their civil and economic rights were denied.

- Perhaps the only consolation from the Reconstruction Era was the fact that Congress was able to restore the Union.

A. Philip Randolph’s planned protest march in the 1940s and 1950s

In response to the racial violence, including the numerous lynching and murders perpetrated by white supremacist groups like the KKK, civil rights movements and activities picked up steam in the decades after the Reconstruction Era. Many civil rights groups began organized marches and protests to advocate their rights.

One of such organizers was the renowned civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph, who was the founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the Negro American Labor Council (NALC). Back in the 1940s, Randolph had made plans to organize a protest march on Washington. With the help of another African American civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, Randolph hoped to use the the march to protest the racial discriminatory hiring practices by the military during the Second World War. Randolph and the Civil Rights Movement called on then-U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to effect change. It was slated to start on July 1, 1941, but by June 25, Roosevelt passed the Executive Order 8802, which put an end to discriminatory hiring. FDR set up the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) to properly investigate and address cases of discrimination and neglect of African Americans and other minorities by the New Deal programs.

With the goal met, the march did not take place. However, in the few years that followed, the FEPC found itself deprived of funding by Congress. By 1946, the FEPC had been dissolved.

In response, Randolph planned another march in 1948. Then-U.S. President Harry Truman was compelled to pass Executive Order 9981, which ended segregation in the US Armed Forces. This was a big victory for the civil rights movement; however, the battle was still not yet over.

Randolph and Bayard continued working on other protests and marches. In 1957, they organized the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, where many other notable civil rights activists and Black entertainers like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, Mahalia Jackson were present.

Read More: Greatest African-American Civil Rights Leaders of All Time

Planning phase and the Big Six

In 1961, following instances of racial attacks against activists in the South and President John F Kennedy’s slow push for vital civil right bills in Congress, Randolph and Rustin started planning the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Despite all the changes and Executive Orders signed, there was still a lot of work ahead for Black civil rights group. As more African Americans jumped on the bandwagon, several more protests and marches took place all over the United States.

In 1963, 100 years after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, Randolph decided to organize another march. This time, he sought the assistance of other civil rights groups and leaders of the movement, including Roy Wilkins, Martin Luther King Jr., James Farmer, Whitney Young, and John Lewis. For example, John Lewis was a leader from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), while Roy Wilkins was the president of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Together, the men were called “the Big Six.” Later members also included Walter Reuther, Dorothy Height, Joachim Prinz, Matthew Ahmann, and Eugene Carson.

The organizers of the March also gained support from some white and other black people. The goal was to form a multi-racial coalition to take the fight for economic and civil rights in America to the next level.

It took at least 3 months to organize the March on Washington. Rustin played a huge role during the preparation stage, including assigning people as marshals and training them on how to control crowds without resorting to violence. He also supervised about 200 activists, whose main task was to recruit marches, raise funds, and arrange travel for protestors. They also distributed buttons that had a design of two hands in a handshake with the inscription “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.”

The planners of the March also wrote a manual, which handled all logistics pertaining to the event.

Towards the end of the preparation stage, Rustin estimated that about 100,000 people would attend the march. He also advocated for a powerful sound system, defending his choice by saying, “We cannot maintain order where people cannot hear.”

Leaders of the march in front of the statue of Abraham Lincoln: (sitting L-R) Whitney Young, Cleveland Robinson, A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King Jr., and Roy Wilkins; (standing L-R) Mathew Ahmann, Joachim Prinz, John Lewis, Eugene Carson Blake, Floyd McKissick, and Walter Reuther

JFK’s apprehension

In June 1963, two months to the March, President John F. Kennedy met with group organizers and other civil rights leaders. He shared that he was fearful that the march was going to turn violent, describing it as “ill-timed.” However, Randolph and the other leaders refused to back down, with Dr. King telling the president, “Frankly, I have never engaged in a direct-action movement which did not seem ill-timed.”

Even though JFK had a bit of apprehension about the planned march, the president still lent his support to the organizers. He tasked his brother, Robert, who was then-U.S. Attorney General, to collaborate with the organizers to ensure that all safety precautions were taken.

Why did the March on Washington end at the Lincoln Memorial?

Initially, leaders of the civil rights movement planned to march all the way to the Capitol. However, it was later decided to bring the march to a stop at the Lincoln Memorial – this was undoubtedly a fitting honor to Abraham Lincoln, the U.S. president who issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

The decision to end the march at the Lincoln Memorial was taken so as not to make the mark look like an attack on the Capitol.

Over 3,000 members of the press covered the historic 1963 March on Washington

Threats were dished out to many of the organizers of the March

The planning stage wasn’t smooth and the organizers faced several threats in the months leading up to the March. Some of the activists involved received bomb threats at work or at home.

The LA Times newspaper received a threat that said its building would be bombed unless it called Kennedy a “Nigger Lover.”

On the day of the March, five planes were forced to be grounded following threats of bomb attacks. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), they received a call from a man who threatened to assassinate Dr. King. Similarly, Roy Wilkins received a number of death threats.

The March on Washington and the Events that Occurred

Objectives of the 1963 March on Washington. Image: some leaders of the March on Washington

As slated, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took place on August 28, 1963. Before the protest march, the leaders of the March had drawn up a list of goals that they hoped the march would accomplish. The following are a few of them:

-

Urge US Congress to pass more meaningful civil rights laws.

-

The abolishment of segregation in educational institutions.

-

Providing job training exercises for unemployed people.

-

Establishing a $2/hour minimum wage.

-

Withholding Federal funds from racially discriminatory interventions and programs.

-

Enforcing the Fourteenth Amendment and giving African Americans the right to vote.

-

A wider Fair Labor Standards Act to create more employment avenues.

-

Power to the Attorney General to pass injunctive suits whenever the civil rights of citizens were threatened.

1963 March on Washington, D.C.

Venue & Number of People

Randolph and the other organizers decided to meet at the Lincoln Memorial instead of the Capitol, as they didn’t want the US Congress to feel that they were under attack. It was also befitting to meet at the monument of Lincoln, whose Emancipation Declaration had freed slaves a century ago. Considered one of America’s most historic event and perhaps the most historic march of the 20th century, the March on Washington on August 28, 1963 was aimed at raising support for fair treatment and equal opportunity for Black Americans. The March on Washington in 1963 was attended by more than a quarter of a million people

Although most civil rights marches and protests organized by Randolph and the others had mostly been African American-focused, the group decided that having people of all races marching would communicate a strong message to the US government. But they also had to be selective of the help they received from other groups, especially those that were regarded as Communist groups.

Several people traveled to Washington D.C., either by road, air, or rail. Rustin had earlier estimated that about 100,000 people would attend the march. However, on the day of the March, over 250,000 arrived, consisting of 190,000 African Americans and 60,000 white people. They all converged at the Lincoln Memorial.

The historic event was also covered by some of the biggest broadcasters in the United States, with much of the focus placed on Dr. King’s speech.

Out of the 250,000 people that attended the March, about 58,000 were white

Did you know?

It’s estimated that the March on Washington was covered by over 2800 media men and women.

Famous Speeches at the March on Washington

Despite initial fears of violence, the March proceeded smoothly and very peaceful. There were security forces present to help control the crowds. The only disturbance was caused by members of the American Nazi Party. However, they were quickly routed out by the police.

In that peaceful atmosphere, several of the organizers and other civil rights activists delivered some of their most inspirational and powerful speeches in America’s history. Many speakers took to the stage to deliver uplifting speeches to the masses.

In all, there were 10 speakers on the day, including Josephine Baker, who was a dancer and actress. During his speech, NAACP’s Roy Wilkins shared that fellow activist W.E.B. Du Bois had died in the West African country of Ghana, where he had been living in exile for a while. He had been unwilling to share that information because Du Bois was known to have Communist ties. In his speech, he still acknowledged Du Bois and credited him for being a part of the reason why they had assembled at the Capitol.

Initially, John Lewis had planned on giving a speech that would be critical of President John F. Kennedy for his slow-paced efforts in getting the Civil Rights Acts passed. However, the other leaders advised that his speech be less inflammatory and critical. Therefore, the young civil rights activist decided to focus his speech on supporting the government’s Civil Rights Act with “great reservation.” He encouraged the attendees to “get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes.”

Walter Reuther, who was white, also encouraged all Americans to remain resolute in the fight to end racial discrimination, equality, and freedom. One man named Irving Bluestone, who was a trade union leader, heard two Black women talking about Reuther. When one asked who Reuther was, the other called him “the white Martin Luther King.”

Martin Luther King Jr. was the last to give his speech. While other speakers ‘scrambled’ to speak early least the press leave, Dr. King chose to speak last. His “I Have a Dream Speech” became one of the most famous speeches in American history. The speech is certainly the most famous and impactful giving my a civil rights activist in our nation’s history.

It’s said that King’s speech was initially meant to last for four minutes, but it went on for a staggering 16 minutes. Interestingly, the line “I Have a Dream” hadn’t been part of his speech for the day. He had been prompted by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who had been standing behind him on the podium, to “tell ‘em about the dream”. In Dr. King’s improvised speech, he added what is now the most famous part of his remarks and the March itself. MLK stated, “And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.”

Randolph, Rustin, and the organizers closed the March by reciting The Pledge and bringing forth their demands. They then visited the White House, where they met with John F. Kennedy. Both sides agreed that the March was a success, considering the turnout and the wide media coverage.

Legendary American civil rights activist and Baptist minister Martin Luther King Jr. gave his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. MLK and the more than 250,000 people that had participated in the March were calling for civil and economic rights as well as the end of racial discrimination. To this day, the speech remains one the most iconic speeches in the history of the United States. It is often ranked as the best American speech of the 20th century.

Did you know?

At the time, King’s speech did not get much recognition; however, with the passage of time, the speech, especially the “I have a dream” line, came to occupy a distinct place in America’s history. It is no wonder, the speech is considered one of the greatest speeches in human history.

Musical Performances

Several African American entertainers performed at the march. Mahalia Jackson, who was a gospel singer, sang “I’ve been ‘buked, and I’ve been scorned” and “How I Got Over.” Another black spiritual singer Marian Anderson also performed “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

There were a number of white musicians as well, including Joan Baez and Bob Dyland. Those two musicians performed “We Shall Overcome” and “Only a Pawn in Their Game”, respectively. They also performed “When the Ship Comes In” together.

Renowned African American gospel singer Mahalia Jackson participated in the March on Washington in 1963. On the urging of Mahalia Jackson to MLK to “tell ’em about the dream”, MLK uttered one of the most famous lines in human history – “I have a dream”.

Celebrity Appearances

Aside from the performers and activists, many other American celebrities attended the march. Josephine Baker, Sidney Poitier, James Baldwin, Jackie Robinson, Eartha Kitt, and Lena Horne were some of the African American celebrities that participated in the March on Washington.

Other celebrities of various ethnicities also joined the march, including Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, Paul Newman, Rita Moreno, and Joanne Woodward.

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan performing at the March on Washington

Criticisms

Although the 1963 March on Washington had been a success, some people shared their criticisms. One of the major elements missing at the protest march, and everything that came with it, was the relative absence of women speakers. When the activist Anna Arnold Hedgeman noted that there hadn’t been any female speakers at the march, the male organizers responded by citing their inability in finding female speakers without causing other issues among other women’s activist groups.

It must be noted that activist Daisy Bates, who had been part of the organizers, spoke at the March; however, she spoke about 200 words. Her speech had been in place of another female speaker, Myrlie Evers, who couldn’t make the trip to Washington, D.C. Another woman, Gloria Richardson, had been slated to give a two-minute speech, but when she arrived, she realized that the chair with her name on it had been taken away. She also had her microphone taken away from her after saying “hello” to the crowd. Apart from Richardson, other female activists like Rosa Parks and Lena Horne were taken off the stage before King began his speech. The only other woman to address the crowd proper was Josephine Baker.

The organizers were also criticized for discriminating against people from the middle class. During the planning stage, the organizers had arranged for “Unemployed Worker” to address the crowd on behalf of other unemployed people. But it was removed from the final program.

The American comedian and civil rights leader, Dick Gregory, also criticized the group’s choice of having white performers at the event. Later, Bob Dylan, shared that he wasn’t comfortable with the idea of a white man serving as the face of the Civil Rights Movements.

James Baldwin with Marlon Brando

Read More: 10 Frequently Asked Questions about Rosa Parks

Did you know?

Supporters of segregation, including a man named William Jennings Bryan Dorn, admonished the US government for not just working together with the black civil rights groups, but being heavily influenced by the civil rights activists. U.S. Senator Olin D. Johnson described the event as “…criminal, fanatical, and communistic…”

What Malcolm X had to say about the March on Washington

Malcolm X, the renowned member of the Civil Rights Movement and black nationalist, also shared similar sentiments to that of Gregory. He described the march as “a circus” and accused the organizers of digressing from the main goal of the march. He said that by allowing white influence, the march failed to show the strength and anger of African Americans.

What did the March on Washington achieve?

Kennedy meets with march leaders. Left to Right – Willard Wirtz, Matthew Ahmann, Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Rabbi Joachin Prinz, Eugene Carson Blake, A. Philip Randolph, President John F. Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Walter Reuther, Whitney Young, Floyd McKissick, Roy Wilkins (not in order)

The 1963 March on Washington was considered a successful event, considering the impact it had in the years that followed. Civil rights historians praise the March for sparking a wave of change and conversation across the United States. In short, civil rights for African Americans were foregrounded, with many U.S. lawmakers began making earnest efforts to properly handle the tense racial situation in the country at the time.

Below are some of the major things that the March achieved:

It helped in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968

The demands that the organizers presented to President John F. Kennedy, as well as Dr. King’s speech, played a massive role in getting the Civil Rights Act of 1964 across the finish line. The tragic assassination of Kennedy on November 22, 1963 helped garner support for the act. Kennedy’s successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson, and many members of the Civil Rights Movement were able to get Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which was followed by Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Open racism died down

It was fairly common for black Americans to be openly discriminated against based on race in the early 1960s. With the March on Washington raising so much about the plight of African Americans and other minorities, there was some bit of change with regard to open and blatant racism. Although it didn’t put an end to racial discrimination, publicly displaying racial sentiments became socially unacceptable.

The NFL had its first Black Quarterback

In those days, black quarterbacks were made to switch their position to defensive back or receiver when they were drafted into the National Football League (NFL). The reason behind that rule was the white belief that black people were not smart enough to hold that position. Dr. King’s speech inspired a young high school student named James Harrison to become a quarterback; and with the help of his football coach, he achieved this dream and became the first black quarterback in the NFL.

Future marches

The March on Washington was so inspiring that other anniversary marches set in its memory were organized every five years. For its 20th anniversary, its theme was “We Still Have a Dream…Jobs, Peace, Freedom.” The March celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2013, during the second term of the first black President of the United States, Barack Obama. The president posthumously awarded Rustin and the other key activists with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, a distinguished honor considered the highest in our nation.

During the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, the NAACP, an organization that played an active role in the 1963 March, organized another march at the Lincoln Memorial. This time, Martin Luther King III, son of King Jr., planned to join other activists and black families in a march against police brutality.

There was also a virtual march for participants who couldn’t attend the protest in-person. Like its parent event, the march also featured performances and appearances from African and African American celebrities, including Burna Boy, Stacey Abrams, and Mahershala Ali. King III and several other activists held another march on the 58th anniversary of the march in 2021, advocating for voting rights and statehood for Washington, D.C.

Read More: 7 Major Accomplishments of Martin Luther King Jr.

Other Interesting Facts about the March on Washington

Here are some interesting fun facts about the 1963 March on Washington:

-

Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech was immortalized at the Lincoln Memorial. Visitors to the landmark will find an inscription in memory of that speech.

-

2023 would mark 60 years since the 1963 March on Washington.

-

Several march attendees shared unique ways they traveled to Washington, D.C. A man was said to have arrived from Chicago on roller skates, while another biked all the way from Ohio.

-

In 2013, The US Postal Service released a stamp of the March to commemorate its 50th anniversary.

-

The sound system that Rustin had demanded for the event was sabotaged on the day before the march. The US Army Signal Corps repaired it overnight.

The steps of the Lincoln Memorial from which King delivered the speech is commemorated with the “I have a dream” line inscription