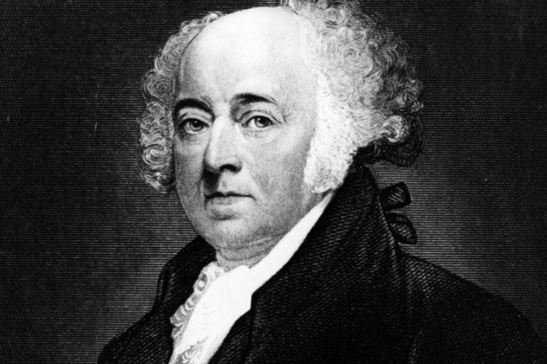

John Adams: Biography, Achievements & Facts

John Adams (1735-1826)

John Adams was an extraordinary political figure during the American Revolution. This Massachusetts-born lawyer and writer succeeded George Washington to become the United States’ second president from 1797 to 1801. Before that, he had served from 1789 to 1797 in Washington’s cabinet as America’s first vice president.

In the course of his illustrious political career, John Adams came to be known for his frankness and bright writing prowess. Along with other founding fathers, he worked extremely hard in the newly formed Continental Congress of the 13 American colonies. But for a few damaging acts, John Adams could certainly have cemented his reputation as arguably the greatest founding father of the United States.

Early Life and Education

On October 30, 1735, John Adams was born in Quincy, Massachusetts (formerly known as Braintree). His parents were John Adams and Susanna Boylston. His father was a deacon, a farmer and shoemaker. Not much is known about Susanna Boylston. It is likely she was a housewife.

Adams was enlisted into the Massachusetts Bar at age 24.

Adams was a very intelligent student, who went on to graduate from Harvard College in 1755. After graduating, he spent some few years teaching at a grammar school. He then proceeded to study law under the guidance of James Putman, a renowned lawyer at Worcester, Massachusetts. At the age of 24, he was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar. The records show that he had a very fulfilling career in his law practice in Boston.

John Adams’ Wife

Abigail Adams – wife of John Adams

On October 25, 1764, John Adams married Abigail Smith: an intellectually astute woman. Abigail was the daughter of a minister. She was raised in an upright manner at Weymouth, Massachusetts. Abigail and Adams were very close and grew fond of each other’s intellectual gifts. She also played a monumental role in Adams’ political career. She was the antithesis to Adam’s somewhat direct and capricious personality. However, the two complemented each other perfectly. Abigail’s wits and charm were there for everyone to see. Thomas Jefferson even once described her as a pragmatic woman with astonishing intellectual reasoning.

John and Abigail’s 54 years of marriage produced 6 children: Abigail “Nabby”, John Quincy, Susanna, Charles, Thomas, and Elizabeth. Most notable of those children was his first son, John Quincy Adams. Quincy followed in his father’s footsteps and became the sixth president of the United States.

READ MORE:

- 6th US President John Quincy Adams – Life and Accomplishments

- 10 Awesome Things You Need To Know About the American Flag

John Adams’ Role in the American Revolution

Adams’ journey to becoming an influential patriot started in the 1760s in his hometown, Massachusetts. He used his reputation as a refined lawyer to advance civil liberties in Boston. He opposed Britain’s imperial control and excessive taxes that blighted the living standards of the American colonies. For example, he was one of the earliest people that were quick in expressing discontent with the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of 1767. These two acts imposed astronomical taxes on things such as playing cards, newspapers, a host of other legal documents, glass, tea, and paper. Adams maintained that the British crown was a purely exploitative regime that did not have the interest of the colonies in mind. His displeasure with the crown was fairly evident in his writing titled: “A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law” (1765).

Legal Counsel to the British Soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre

This Massachusetts-born patriot was an avid believer in the rule of law, equality and fair representation. His principles saw no boundaries. Adams even took it upon himself to represent the perpetrators of the Boston Massacre during their trial. The defendants, eight British soldiers, and their captain were accused of killing five Americans.

He shocked everyone, including his peers, by showing that every individual, regardless of their political affiliations, deserved the right to have a legal counsel. He made such a strong legal argument during the case. In the end, he was able to secure exoneration for some of the accused soldiers. In the eyes of some patriots, this was a flagrant betrayal of the colonies’ cause. However, the true believers of legal rights and justice upheld his decision as admirable.

None of those public criticisms dampened Adams’ rigorous campaign against King George III’s rule and the various oppressive Acts of the British Parliament.

Delegate to the Continental Congress

In 1774, patriots and representatives from 12 out of 13 American colonies assembled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This dedicated group of people formed the first Continental Congress.

John Adams was part of the newly elected delegates that represented Massachusetts at the First Congress in 1774. They resolved to engage with George III diplomatically. Unfortunately, all their appeals fell on deaf ears. John Adams, along with his cousin, Samuel Adams, increasingly got frustrated afterward. They began to push for not just tax removals but also complete independence of the American colonies.

Adams and his fellow delegates would later reconvene in 1775 for the Second Continental Congress. It was during this deliberation that Adams nominated George Washington to lead the newly formed Colonial Army. He believed that there was no better person than General George Washington to lead them militarily in the American Revolutionary War.

Read More:

- Who were the Founding Fathers of the United States?

- 15 Great Achievements of George Washington

- John Hancock – Biography and Crucial Facts

Drafting and adopting the Declaration of Independence

In a Second Congressional meeting in 1776, Congress selected John Adams to be part of the Committee of Five. The committee was asked to draft a document that would justify the split from the British Empire. The committee’s four other members were Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, Robert R. Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson.

Adams, in turn, nominated Thomas Jefferson to be the main draftsman of the Declaration document. He and Jefferson worked closely together to prepare the document. After about three weeks, the committee submitted the document to Congress. Adams successfully rallied Congress to vote and approve Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration. After several debate sessions and banters, Congress approved the Declaration document on July 2, 1776. John Adams was filled with happiness none like any other delegates in the chamber. He appended his signature to the document on July 4, 1776.

Diplomatic works in Europe

For the next couple of years after the Declaration, Adams continued to serve diligently as a Massachusetts delegate to the Continental Congress. He immersed himself extensively in Congress’ foreign relations proceedings. At some point in time, he was on about 90 Congressional committees. In 1776, he designed a Model Treaty that later formed the foundation for the 1778 Treaty of Alliance and the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with France. The treaty served to build stronger trade, political and cultural bonds with France – bonds that would thwart or deter any future attack by Great Britain.

Additionally, he was put in charge of the Board of War and Ordinance. The board was mandated to solicit for vital funds from European countries to build the American Navy.

In 1778, John Adams was picked as a diplomat to serve with Benjamin Franklin and John Jay in France. Their objective was to promote America’s interests. He and Franklin developed an effective partnership during the treaty negotiations with France in 1778. Their natural traits complemented each other perfectly. Franklin had the charm and the most delicate of touches when dealing with foreign partners. This often paved the way for Adams to come in with his hard and upfront talk.

Adams also embarked on several diplomatic trips to places like the Netherlands and Venice. His time in the Netherlands allowed him to negotiate on April 19, 1782, with the Dutch. Adams signed peace and commerce deals with them in October 1782.

Adams’ tireless efforts served as a foundation to what would later lead to the successful negotiation of the Treaty of Paris in 1783. This treaty in effect ended the Revolutionary War with Great Britain.

The Massachusetts Constitutional Convention

Amidst the negotiations and deals that were struck in Europe, John Adams frequently stopped by in his hometown to work on the Massachusetts Constitution in 1779. His draft was such a phenomenal work that it became the template for other US states’ constitutions as well as the United States Constitution itself. The Massachusetts Constitution holds the honor of being the oldest surviving written constitution.

A major instrumental document that the State of Massachusetts used was John Adams’ comprehensive book titled: “Thoughts on Government”. Published in 1776, this guidebook about constitution drafting was read by many across the colonies. It contained details about effective people representation and separation of powers. Also, many other states came to rely strongly on this book during the drafting of their constitutions.

The First United States’ Ambassador to Britain

John Adams served as the first American ambassador to Britain.

Adams served as the first American minister to Great Britain. He was stationed in London from 1785 to 1788. It was also around this time that Thomas Jefferson was posted to replace Benjamin Franklin in France. Adams and Jefferson stayed in touch and their bond grew much stronger. On the work side of things in Europe, Adams and Jefferson effectively collaborated to secure a $400,000 loan facility from the Dutch.

The First Vice President of the United States

John Adams’ work on the Paris Treaty and other diplomatic arrangements received positive acclaim from the American public. Upon his return to America in 1789, he was instantly tipped to occupy the presidency. This did not, however, happen as George Washington was elected as the first president of the United States. Adams came in second during the election.

Per the rules at that time, he had to settle for the vice president. He stayed on as vice president from 1789 to 1797. The office was a largely ceremonial role.

Adams grew very frustrated throughout his two terms as vice president. This was because he felt that his expertise and skills were underutilized in the position. He described the office as: “the most insignificant office”. His only serious role as vice president was to head the Senate and handle the parliamentary aspect of George Washington’s government.

He and Washington, who were both Federalists, had similar views and philosophies about how the government should function. Also in their team was Alexander Hamilton, America’s first treasury secretary. Inclusive in Washington’s first cabinet was Adams’ long-time friend, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was appointed by Washington to serve as the nation’s first Secretary of State.

Conflict with Thomas Jefferson

As time went by, Jefferson and Adams began to move in different directions philosophically. Jefferson headed a splinter group that would later be called the Democratic-Republicans. They believed that the various states in the Union were entitled to greater control of their affairs. They lobbied Washington’s administration into having a more decentralized federal government.

On the other hand, Adams’ views, along with Alexander Hamilton’s (head of the Federalist Party), ran in complete opposite to that of Jefferson’s. Their party’s philosophy was geared towards a stronger and more centralized federal government. Also, they maintained that the United States was duty bound to stay neutral in the affairs of Europe. The 1793 Neutrality Proclamation, which was supported by Adams and his Federalist Party, successfully forced the U.S. out of the 1778 alliance with France. The Americans took great care not to be seen by either France or Britain as supporting one side.

The rivalry between Adams and Jefferson got to a point where the latter had to resign his position as secretary of state in 1793.

Presidency from 1797 to 1781

After Washington’s retirement, Adams contested in the 1796 election and defeated Thomas Jefferson by 71 to 68. This meant that Jefferson, who had the second highest number of votes, became the vice president. After their inaugurations, the two men tried to patch things out; however, it just did not work for them. Philosophically, they were poles apart from each other.

Historians believe that Adams’ mishaps during his presidency were further complicated because he retained most of George Washington’s cabinet. In his defense, he maintained Washington’s staff for the purposes of smooth transitioning. He basically stuck to the values and principles of his predecessor. Most importantly, he stood his ground and towed a neutral path in Europe.

Another point worth stressing is that Adams simply struggled to fill the big shoes left behind by Washington. Even long after Washington left office, the entire political and military apparatus of America still maintained a cult-like admiration for Washington. It is, therefore, safe to say that the American public continuously compared Adams to Washington. Many even doubted his ability to properly handle the brief naval war (also known as the Quasi-War) between the U.S. and France from 1798 to 1800.

To top this, Adams struggled to keep his Federalist Party together. Cracks began to appear among the leadership of the party. Some of the Federalist members accused him of being too weak in handling any crisis.

The XYZ Affair

In 1797, President Adams dispatched a group of diplomats to negotiate a cessation of hostilities between France and Britain. Fortunately, that trip briefly boosted Adams reputation domestically. The French officials outrageously demanded bribes and loan facilities from the U.S. delegation. The scandal (popularly known as the XYZ affair) created a lot of anti-France sentiments in America.

Adams’ Federalist Party called for war with France. However, and to the dismay of the general public, he opted not to do so. He pursued a peaceful means to settle the conflict. He sent a second delegation to France. He must have known that not engaging the French militarily was going to make him unpopular. Regardless of that, he stood by his principles. Unsurprisingly, this action of his damaged his approval ratings among the Federalists as well as the general public. But in the long run, it saved the United States from engaging in a costly war that could have dragged on for years.

John Adams’ greatest pitfall: The Alien, Sedition and Naturalization Acts

Another uncharacteristic move of Adams came in the year 1798. The Alien, Sedition, and Naturalization Acts bankrupted whatever reputation that he had among the American public by then. The acts were politically driven moves by the Federalist-dominated Senate to cripple dissent and free speech from the opposition Democratic-Republicans.

For example, the Sedition Act gave the government the power to deport any foreigner who spoke harshly against the executive or parliament. Additionally, such moves resulted in massive fallout between Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The latter considered the acts as insulting to the ideals of democracy and civil liberties.

It must be noted that it was the Federalist-controlled Congress that forced Adams into signing those acts. He would go on to regret this action of his. This was because the acts reminded Americans of the oppressive times under Britain’s rule. This did not augur well for Adams in the following election.

Adams loses the 1800 Presidential Election

By 1800, the divisions within the Federalist Party were palpable. Adams still had not resolved his long-standing philosophical dispute with the Hamiltonians (those who supported Alexander Hamilton). And the party, as well as the country, was just recovering from the death of George Washington in 1799. One could say that the Federalists were in disarray. The presidency was therefore for the taking by much more organized Democratic-Republicans.

John Adams was defeated by Thomas Jefferson in the 1800 election by 65 to 73. The tension between Adams and Jefferson resulted in the former not attending the presidential inauguration of Jefferson in 1801.

Prior to leaving office, Adams made some last-minute appointments of permanent public officials. The most prominent of those appointments was John Marshall, his former secretary of state. Initially, Marshall’s appointment as the fourth Chief Justice of the U.S. drew widespread criticisms from Jefferson. Jefferson condemned them as “overnight appointments” that were aimed to keep the Federalist Party at the helm of power long after Adams left office.

Retirement and Reconciliation with Jefferson

After his presidential tenure, Adams headed straight for Quincy, Massachusetts. He retired into farming and writing books and letters. He lived together with his wife Abigail until her death in 1818.

In 1812, Adams and Jefferson reconciled their differences. The two former presidents exchanged a total of 158 letters. They maintained a very close-knit relationship for the remainder of their lives. It is said that the reconciliation between Adams and Jefferson was made possible by a Philadelphia physician, Benjamin Rush.

Also, Adams was fortunate to have witnessed the 1825 presidential inauguration of his son, John Quincy Adams as the sixth President of the United States.

John Adams quotes

John Adams’ Death

About a year after his son’s presidential inauguration, John Adams passed away on July 4, 1826, at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts. He was 90 years old. His long-time friend/foe, Thomas Jefferson died on the same day as well. Another surprising thing is that the very date of their deaths fell exactly on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

The people that were by Adams’ side said that the last words he uttered were: “Thomas Jefferson still survives”.

John Adams’ Political Philosophy

Time in Europe afforded Adams the opportunity to study a wide range of historical documents about European politics and governance. He wrote three voluminous books that were titled: “A defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America (1787)”. The book contained quotations and personal observations from both the U.S. and Europe. The fourth volume of the series was published in 1790 as: “Discourses on Davila”.

In those books, Adams argued that revolutionaries that promised an Utopian society were completely delusional. According to him, their goals sounded reachable and promising theoretically. However, in reality, those promises were unattainable. He observed that the class struggles that existed in European monarchical societies were bound to blight the fledgling United States.

Adams believed that it was the government’s duty to control the natural excesses of those elites. By doing so, the government would be able to create a very stable political system that is close to fair and just.

As a result of these and many more other views, John Adams opened himself up to severe criticisms. Some of his critics thought that he was pro-monarchy and aristocracy in America. Some even went as far as saying that Adams wanted to return America to the British rule.

History has proved that, in so many ways, John Adams was actually right about the inevitability of aristocrats rising up in every form of society.

His desire was to have a government that was independent enough and not easily swayed by the wishes of the few elites in America. In today’s world, this phenomenon has reared its head in the form of capitalism and Wall Street bankers. Governments across the world are on a losing struggle with those very few and very powerful non-elected members of the ruling class.

Adams knew wholeheartedly that the government could not completely stay free from those elites. However, what he believed in was a situation where the government could somehow direct the ambitions of these groups into the greater good of the whole nation. For this, he maintained that the executive must have ample power that would enable them to keep in check those groups.

The kind of power Adams referred to was often misunderstood to mean the kind kings and queens possessed in Europe. Luckily, in the last half of the 20th century, this misunderstanding or misinterpretation of Adams’ political philosophy was rectified due to a greater circulation of his correspondences and writings.

Adams was simply a brilliant man who truly understood the psychological nature of political systems across nations. He even correctly predicted that the French Revolution would inevitably result in years of civil unrest that would in itself later necessitate the rise of a maniacal ruler. Perhaps the reason why he did not attain the highest acclaim from his peers and the public was because of his unconventional manner of dealing with things.

John Adams quotes

Trivia—John Adams’ Nicknames

As a result of him being slightly overweight, John Adams was nicknamed “His Rotundity”. He was also referred to as “Bonny Johnny”. And for his massive role and dedication to the admirable cause of America’s independence, Adams was sometimes called “The Atlas of Independence” or “The Colossus of Independence”. Other famous nicknames that he had were the “Duke of Braintree” and “Old Sink and Swim”.

FAQs

Below are brief answers to some common questions about John Adams:

When and where was John Adams born?

This US politician was born on October 30, 1735, in Braintree (now Quincy), Massachusetts.

Who were his family members?

Adams married Abigail Smith in 1764. They had five children: Abigail, John Quincy (who would become the 6th U.S. president), Susanna, Charles, and Thomas Boylston.

What was his role in the American Revolution?

Adams was a strong advocate for American independence. He served in the Continental Congress, assisted in drafting the Declaration of Independence, and was instrumental in persuading the Congress to adopt the declaration.

What were some notable events during his presidency?

His presidency saw the XYZ Affair, a diplomatic controversy with France, and the subsequent quasi-war with France. The Alien and Sedition Acts, controversial laws aimed at silencing political dissent, were also passed during his term.

How did he handle foreign relations?

Adams is often credited with preventing a full-scale war with France during his term. Despite pressure to go to war, he pursued a peaceful solution, though it was politically unpopular.

What was his relationship with Thomas Jefferson?

Adams and Jefferson had a complex relationship. They were friends, collaborators, and then political rivals. While they had a falling out during their presidential terms, they later reconciled and maintained a correspondence until their deaths.

When and where did he die?

John Adams died on July 4, 1826, in Quincy, Massachusetts. Interestingly, Thomas Jefferson died the same day.

What is John Adams known for?

Adams is known for his role in the American Revolution, his diplomacy during the early years of the republic, and his commitment to the rule of law and the U.S. Constitution. He’s also recognized for his writings, including letters to his wife, Abigail, which provide insight into the times and their personal lives.

Did he own slaves?

No, John Adams did not own slaves and was opposed to slavery. He often voiced concerns about the institution, though he did not take strong public actions against it while in office.

Quick Summary of John Adams Achievements

We conclude this article by providing 11 astounding achievements of John Adams. They are:

- One of the first campaigners against the Intolerable Acts of 1774 that ultimately led to the American Revolutionary War.

- He cast aside his political bias and represented the British soldiers accused in the Boston Massacre.

- Played a phenomenal role in drafting the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

- He worked on the Massachusetts Constitution in 1779

- Adams delicately handled and resolved the Quasi-War with France.

- He signed the Paris Treaty of 1783 that ended the Revolutionary War with Britain.

- America’s longest-serving Chief Justice, Justice John Marshall, was appointed by John Adams.

- He was the first former president to have his son become president. Quincy Adams became the sixth U.S. president in 1824.

- John Adams completely detested slavery and never owned slaves.

- He played a massive role in building America’s Navy and army capabilities.

- The first occupant of the White House was Adams. He moved into the residence on November 1, 1800, slightly before he left office.

Conclusion

John Adams’ straightforward approach to politics was crucial during the formative years of the United States of America. His honesty, mixed with a level of intellectual sophistication, helped secure several peace treaties with European countries. Although his brief four-year tenure as president of the United States was beset by an attempt to suppress free speech, his role during tremendous geo-political crisis deserves our earnest admiration.

John Adams quotes