Pompey the Great: History, Major Facts & Greatest Accomplishments

Pompey the Great (died 48 BC in Pelusium, Egypt), Roman Republic General and statesman, came to prominence in the 1st century BC with a series of astounding military campaigns, particularly against Gaius Marius (157-86 BC), Roman Republic General and consul, during the Social War.

Usually regarded as one of the most distinguished generals of the Roman Republic, Pompey had successes in Spain, which was then followed up by his decimation of Roman slave-turned-rebel Spartacus and his army in 71 BC. He also brought a bit calm and order in the Mediterranean Sea after getting rid of the pirates that frequented eastern Mediterranean in 67 BC. However, the feat that etched him into the annals of history came in 61 BC, when he constituted the First Triumvirate with Marcus Licinius Crassus and Julius Caesar.

What else was this triumvir Pompey the Great most famous for? What were some of his major contributions to the Roman Republic and future empire?

In the article below, WHE presents the life, family history, and major achievements of Pompey the Great – one of the most known personalities of the Roman Republic era.

Quick facts about Pompey the Great

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, known in English as Pompey the Great

Born: Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus

Date of birth: September 29, 106 BC

Place of birth: Picenum, Roman Republic

Died: September 28, 48 BC

Place of death: Pelusium, Egypt

Cause of death: Assassination by courtiers of Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII of Egypt

Buried: Albanum, Italy, Roman Republic

Father: Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo

Children: Sextus Pompeius Magnus Pius, Gnaeus, Pompeia

Spouses: Cornelia Metella (52-48 BC), Julia (59-54), Mucia Tertia (76-61 BC), Aemilia (82 BC), Antistia (86-82 BC)

Positions held: Consul (70 BC; 55 BC; 52 BC); Governor of Hispania Ulterior (58-55 BC)

Epithets: Pompey the Great

Pompey’s family of influential nobles

Pompey was born on September 29, 106 BC in Rome into a family of senatorial nobility. His family is said to have had ties with many Greeks. Due to this connection Pomepey spoke fluent Greek.

Like any child born into a noble family, Pompey received a normal education. He also spent time understudying his father, Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo (c. 135-87 BC), who taught Pompey a great deal of things, including military strategy and political philosophy. His father was the first person from his family to attain a very influential status in politics, rising from praetor (magistrate) to consul in 89 BC. Strabo, who went by the nickname novus homo (new man), was described as a ruthless politician and military commander who fought in the Social War (91-87 BC), a war between the Roman Republic and its allies in Italy over citizenship for the Italian allies. Pompey served under his father during the final few years of the Social War (91-87 BC). For his efforts in the war, Strabo was honored with a triumph.

During his father’s time in power, the Pompey family considerably increased their wealth and owned many possessions in areas that are now in present-day eastern Italy.

The first Roman civil war

When the first full-scale civil war in Roman history broke out in 88 BC, it pitted two very influential Roman politicians and generals – Lucius Sulla and Gaius Marius – against each other. Pompey’s father, Strabo, threw his support behind Marius’ faction. Upon the death of his father during a siege of Rome by Marius’ faction in 87 BC, Pompey switched his allegiance to General Sulla.

Children and wives

According to ancient historians, Pompey married about five times. As stated above, his first marriage was to Antistia, the daughter of a judge. He then divorced Antistia in 82 BC in order to marry Aemilia, Sulla’s stepdaughter. His marriage to his third wife, Mucia Tertia, ended in a divorce, after he accused her of being unfaithful. They did however have three children – Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Pompeia Magna, and Sextus Pompey. Pompeius was executed in 45 BC, while Sextus famously rebelled in Sicily against Emperor Augustus.

His fourth and fifth marriages were to Julia, Caesar’s daughter, and Cornelia Metella, daughter of Metellus Scipio, respectively. His fourth wife, Julia, died during childbirth in 54 BC.

Sulla’s Civil War (83-81 BC)

With vast resources and estate that he had inherited from his father, Pompey, then in his early 20s, supported the cause of Lucius Cornelius Sulla’s fight against Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna. The struggle, i.e. Sulla’s Civil War, took place from 83 to 81 BC. Following a resounding victory by Sulla’s forces at the Battle of the Colline Gate in 82 BC, Sulla went on to become the Dictator (chief magistrate) of Republic. With the three legions that he had raised in Picenum, Pompey led his men gallantly during the war, helping Sulla successfully march on Rome and remove the Marians from power.

Following Sulla’s march on Rome and later appointment as Dictator, Pompey was rewarded handsomely by Sulla. The general even convinced Pompey to divorce his wife Antistia in order to marry Aemilia, Sulla’s stepdaughter. Aemilia sadly passed away in 82 BC during childbirth. Pompey then married Mucia Tertia, who bore three children for Pompey – Pompey the Younger (Gnaeus Pompey), Pompeia Magna, and Sextus Pompey.

Pompey’s campaign in Sicily and Africa

Another stellar feat of Pompey came during his military campaigns in Sicily and Africa between 82 and 81 BC. Following Sulla’s seizure of power from the Marians in Rome, a good number of the Marians fled to places in Sicily and Africa. In Sicily, Roman general Marcus Perpenna Vento offered them a safe haven. One of such Marians was Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, a former co-consul with Lucius Cornelius Cinna.

Under the instructions of Sulla, Pompey marched on Sicily with a big force, forcing Perpenna to leave Sicily. Once Sicily was taken, Pompey paraded Carbo before the tribunal and a death sentence was passed on Carbo. Due to the severity of the punishment exacted on the Marians in Sicily, he came to be called adulescentulus carnifex (adolescent butcher).

After leaving his brother-in-law Gaius Memmius in charge of Sicily, Pompey sailed to the Roman province in Africa, where many Marians had found refuge. In Africa, he fought against Gnaeus Domitus Ahenobarbus, the son-in-law of Cinna. Pompey’s winning streak was perhaps one of the reasons why several thousands of the enemy troops joined his cause. The young general ultimately defeated and killed Domitus at the Battle of Utica in 81 BC. Several allies of Domitus, including King Hiarbas of Numidia, were killed by Pompey.

Why Sulla tried to deny Pompey a triumphal celebration

Upon returning to Rome, Pompey was given a rousing welcome, having successfully taken Sicily and the province of Africa from the Marians. Sulla even bestowed the title Magnus (the Great) upon Pompey, who at time was still in his mid-20s. According to historians, Pompey’s relative young age was the reason why Sulla denied him a triumph procession. Perhaps Sulla did not want such a young general as Pompey to have all the honors in Rome.

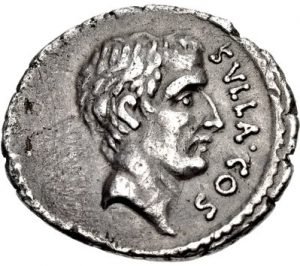

Portrait of Sulla on a denarius minted in 54 BC by his grandson Pompeius Rufus

Pompey’s first triumph and his four-elephant drawn chariot

However, Sulla later rescinded his decision and allowed Pompey to have his triumph. Perhaps Sulla was afraid of upsetting Pompey, whose power and reputation in the Republic was rising very fast. Wanting to make a big splash in Rome, he attached his triumph chariot to the four elephants that he had brought from Africa. It’s been stated that the city’s gate was too narrow to allow the elephant-drawn chariot to make it through. Pompey was then forced to use his horses, much to his disappointment.

Defeated Marcus Perperna in the Sertorian War (80-72 BC)

Beginning around 80 BC, the last remnants of Cinna-Marian supporters in Hispania (i.e. the Iberian Peninsula provinces), began to rebel against the officials placed by Sulla in the region. Led by Roman general and statesman Quintus Sertorius, the rebels resorted to guerrilla warfare. With the help of troops from the Celtiberians and the Lusitanians, Pompey was moved in with his troops to give support to the proconsul Metellus Pius of the province of Hispania Ulterior. Sabotaged by the machinations of Marcus Perperna, Sertorius came under increasing pressure as he began losing due to defections to Pompey’s army. After a series of losses to Pompey’s forces, Sertorius was assassinated by Perperna, who was then defeated by Pompey in 72 BC. Pompey had Perpena executed. In the end, the rebellion was put down.

Upon his return to Rome, the Senate honored Pompey with a triumph, his second in the space of a decade.

The Gladiator War (73-71 BC)

Also known as the Third Servile War, the Gladiator War saw Roman slaves led by Spartacus rebel against the Roman Republic. The war, which spanned from 73 to 71 BC, was the last and most devastating of the three slave rebellions. It began at a gladiator school in Capua in 73 BC, when almost 80 slave gladiators made a break for it. In the two years that followed their numbers had increased to over 100,000 forces. For a time, there was nothing that Rome could do to stop the rebels from rampaging across Italia with freedom.

With Rome struggling to quell the rebellion, Pompey was called by the Roman Senate. Before Pompey could face them, Roman general and statesman Marcus Licinius Crassus had successfully decimated the Spartacus and his army of slaves in 71 BC. Although Crassus was in fact the general who did most of the heavy lifting, Pompey still got a bit of credit for the victory during the Gladiator War. The two men used the military victory to boost their political careers in Rome.

The acrimony between Pompey and Crassus

Pompey and Crassus, who was the richest man in Rome at the time, were elected to the consulship positions in 70 BC. Owing to the bit of bad blood between Pompey and Crassus, their time as consuls was an uneventful one as they disagreed on almost every issue. Some historians state that the two men fought over honors. Crassus was not too pleased by Pompey’s taking credit for the victory over Spartacus and the slave army during the Gladiator War. Out of suspicion for each other, Pompey and Crassus did not disband their armies, leaving them on the outskirts of Rome. The two rivals ultimately shook hands in public, sending a message to the public of their readiness to put aside their differences.

Achievements of Pompey the Great

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey the Great, ranks among the greatest generals and politicians of the Roman Republic era. | Image: A denarius of Pompey minted in 49–48 BC

His military prowess and generalship were described as very brilliant. This explains why he chalked so many feats. For more than two decades, he was the most leading and powerful general in the Roman Republic. He may have not had the visionary mind like Caesar, but Pompey was very efficient in majority of his military campaigns. He was praised for being an exceptional military strategist and organizer. These skills were some of the reasons why he was so successful in his campaigns in the east.

The above explains why Greek historian Plutarch described Pompey as the Alexander the Great of Rome. The historian also bemoans how the politicians in Rome maligned Pompey and orchestrated the downfall of the general.

Some historians have noted that had Pompey had the political acuity as Caesar’s, he most definitely would have gone to establish himself a monarchy in Rome.

Pompey the Great and the pirates of the eastern Mediterranean

Beginning around the first century BC, the activities of pirates in the Mediterranean had become a thorn in the flesh of Rome. The Republic was losing big due to pirates operating with impunity, especially in the eastern Mediterranean. Those networks of pirates not only plundered the coastal regions of the Republic, but they also disrupted vital supply lines, which became intolerable for Rome’s allies.

Prior to Pompey coming into the fray Roman generals like Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus and Marcus Antonius Orator had all campaigned against the pirates, especially those off the coast of Cilicia (modern-day southern Turkey). With support from the tribune Aulus Gabinius, Pompey received enough power and resources and ships from the Republic to go after the pirates. Pompey divided the Mediterranean into areas, with each area given to a lieutenant to handle. In less than two months, Pompey had successfully brought a bit of order to the western Mediterranean coast lines. This was then followed by removal of pirates in the eastern Mediterranean. He also attacked the pirates that had fled to Cilicia.

Pompey’s success in the Mediterranean was well received by the people, as supply lines were restored for the transportation of vital goods. Uncharacteristic of him, he did not execute the pirates that he had surrendered to him; instead he resettled many of them in cities such as Soli, Dyme and the inner parts of Cilicia. He was wise enough to know that the pirates were engaged in the nefarious work that they did because of the high level of poverty in their respective countries, which in turn was caused by the years of civil wars and strife of the era.

All in all, Pompey showed extraordinary generalship and seized several hundreds of ships from the pirates; he also destroyed many of their weapons and ship making materials. According to Greek historian Appian of Alexandria (c. 95 – c. 165), about 10,000 pirates lost their lives in Pompey’s war against the menacing network of pirates in the Mediterranean.

Showed an extraordinary generalship during the Third Mithridatic War (73-63 BC)

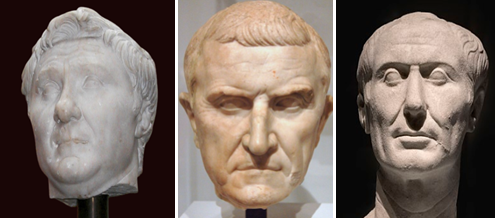

Pompey conquered the eastern kingdoms in the Third Mithridatic War (73-63 BC) before proceeding to reorganize the eastern provinces of the Republic. Image: Roman statue putatively depicting Pompey, at the Villa Arconati a Castellazzo di Bollate (Milan, Italy), brought from Rome in 1627 by Galeazzo Arconati

The Third Mithridatic War pitted Roman Republic against Mithridates VI, the king of Pontus, and Tigranes the Great, the king of Armenia. Initially it was the Roman general and statesman Lucius Licinius Lucullus (118-57 BC) – a devout associate of Lucius Cornelius Sulla – who led the Roman forces. However, increasing dissent among some top politicians in Rome over Lucullus’ handling of the situation resulted in Pompey receiving command of the Roman forces in the war. Thus, many of the areas under the command of Lucullus were transferred to Pompey. This came in spite of strong opposition from the optimates, a conservative group of Roman politicians, who were not so pleased that Pompey received such an enormous power. Neither was Lucullus, who described Pompey as a “vulture” who took credit for people’s works, citing special emphasis to the Spartacus War.

With support from leading politicians and statesmen like Cicero (known as Marcus Tullius Cicero) and Julius Caesar, Pompey went on to defeat Mithridates VI and his allies, thereby conquering the eastern kingdoms. Pontus and Syria became Roman provinces, while Judea became a client state of Rome. The war also brought an end to the Pontic Kingdom.

Reorganization of the East

After defeating King Mithradates IV in 63 BC, Pompey went on to reorganize the eastern provinces of the Republic. This feat of his was perhaps his greatest. It also earned him a third triumph in Rome. He placed many Hellenised towns that he had liberated under the Roman province of Syria, which lied on the coastal strip from Gaza to the gulf of Issus.

It must be noted that those towns were given some form of autonomy. The western coastal area of the Kingdom of Pontus was put together with Bithynia, forming the Roman province of Bithynia et Pontus. Many of the conquered parts of Mithridates were made client states of the Republic.

Pompey also reorganized the province of Cilicia (in what is today the southern coast of Turkey) into six parts – Phrygia, Lycaonia, Pisidia Isauria, Pamphylia, Cilicia Aspera, and Cilicia Campestris. He then made sure that the people he left in charge of those areas swore loyalty to the Roman Republic. For example, Aristarchus was placed in charge of Colchis (located on the coast of the Black Sea); Antiochus received Commagene; and Osrhoene was given to Abgar. Pompey allowed Tigranes to stay on as king of Armenia.

Following his reorganization of the East, he returned to Rome and was honored with a triumph in 61 BC. That was his third triumph, and he was only 45 at the time. Rumors swelled that Pompey would match his army on Rome and become its king; however, he disbanded his army and paid the soldiers handsomely. Pompey’s reputation was at an all-time high.

18th-century depiction of the third triumphal celebration for Pompey the Great

According to Plutarch, Pompey claimed that he restored order to 900 cities in his illustrious military career. He also founded more than 39 cities. What all that meant was increased tax revenues (by about 70 percent)for the Roman Republic. This is not to mention the copious amounts of treasures that he captured during his campaigns. He also amassed an enormous amount of personal fortune in the process. There were some claims that Pompey’s wealth dwarfed Crassus, who at the time was known as the richest man in Rome.

Read More: Ancient Roman Gladiators – History and Major Facts

Formation of the First Triumvirate (61- 54 BC)

Pompey, Caesar and Crassus formed the First Triumvirate in order to get their policies passed in the Senate. Their secret alliance in effect nullified every form of opposition towards them. First Triumvir (L-R): Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar

Following his conquest of the eastern kingdoms and the reorganization of the east, Pompey asked the Senate to sanction the work he had done in the east. Fearing his growing power and popularity, some senators, particularly members of the conservative faction, the optimates, refused ratifying the acts of his settlements in the east. Therefore, Pompey could not get to do the things that he wanted since the Senate had become a stumbling block in his way. That all changed when Roman general and statesman Julius Caesar returned to Rome in 60 BC. Caesar was a way more gifted politician than Pompey, hence the latter sought to use it to his advantage. Caesar also knew that he stood to benefit a great deal from Pompey’s enormous resources and public reputation. So the two men decided to form an alliance that also included Crassus, Rome’s wealthiest man.

That alliance came to be known as the First Triumvirate. The goal was to use their combined strengths to push their political and military agenda in the Senate. The optimates stood no chance against the First Triumvirate. With the help of Caesar, Pompey was able to get his acts of settlements in the east passed in the Senate. Caesar then became governor of Gallia Cisalpina, Illyricum and Transalpina.

To cement their informal pact, Pompey married Julia, the daughter of Caesar, in 59 BC. With relatively few conflicts among the triumvirs, the First Triumvirate was renewed in 56 BC at the Lucca Conference, where it was agreed that Caesar would continue to hold the Gaul, while Pompey would have Hispania and Crassus Syria.

Pompey versus Julius Caesar

Perhaps wanting to outshine Caesar, who had tremendous success in the Gallic Wars (58-50 BC), Crassus marched on the Parthian Empire, but was met with a humiliating defeat. Crassus died in 53 BC at the Battle of Carrhae. His death put a huge strain on the Triumvirate, which was still reeling from the death of Julia in 54 BC.

Some historians, particularly Plutarch, noted that perhaps the only thing that kept the Triumvirate from breaking apart was the presence of Crassus, who was feared by both Pompey and Caesar. With Crassus gone, the First Triumvirate collapsed. Pompey perhaps got envious of Caesar and his heroics in Gaul. As Caesar’s influence increased in the Republic, Pompey’s kind of waned. Amidst all that, the tribune Lucilius tried to convince his fellow politicians to elect Pompey dictator. However, some politicians opposed this. Pompey’s desire to be consul in 52 BC created lot factions to appear, and with that violence became the order of the day. This was perhaps the reason why some politicians, including the optimates, called on the election of Pompey as dictator so he could restore order.

A compromise was reached, and the Senate elected Pompey as the sole consul in 52 BC. In that position he was able to restore order in Rome. The support Pompey had from the public increased tremendously after he recovered from an illness in 50 BC. With winds in his sail, Pompey reasoned that the time was ripe for him to oppose Caesar and weaken Caesar’s support base among the optimates. However, Pompey acted too late by which time Caesar had amassed his army and crossed the Alps and set his sights on Rome. Caesar threatened to march on Rome should Pompey not disband his army. After a failed attempt by some leading politicians to get the senate to declare Caesar public enemy, calls increased for both Pompey and Caesar to disband their armies.

When it became apparently clear that Caesar did intend matching on Rome, the senate and Pompey began making preparations to defend against Caesar’s troops. However, the Senate’s preparations were inadequate. Panic ensued owing to the speed at which Caesar was heading towards Rome.

Pompey did not want to negotiate with Caesar, as he believed that such a move would make Caesar more powerful in future. He then fled with his troops to Campania, where he hoped he stood a better chance of facing Caesar. He would later decide to leave Italy entirely and sail to Greece, where he began writing letters to rulers in the east, asking for their help.

In the end, Caesar’s Civil War culminated in Pompey facing off against Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC in central Greece. Even though Pompey’s forces vastly outnumbered Caesar’s legions, Pompey was resoundingly defeated, forcing Pompey to flee his camp wearing the clothes of an ordinary citizen. With very few allies left on the western Mediterranean, Pompey sailed to Egypt, hoping to receive the support of Ptolemy XIII of Egypt.

How did Pompey die?

As Pompey approached Egypt, Ptolemy XIII’s courtiers held a council meeting to decide what to do with Pompey. The choices were either to drive Ptolemy away and allow Caesar continue pursuing the general or welcome Ptolemy. With regard to the latter choice, Theodotus of Chios, Ptolemy’s chief advisor, noted that welcoming Pompey with open arms risked incurring the wrath of Caesar. It also meant that Ptolemy would in effect become the ruler of Egypt. Theodotus advised that Pompey be eliminated the moment his ship hit the shores of Egypt. That way Egypt would not have to contend with Caesar’s fury.

And so, when Pompey arrived on the shores of Egypt on September 28, he was murdered by the head of Egypt’s army Achillas and two other assassins. Prior to disembarking, Pompey’s associates and his wife Cornelia suspected the Egyptians were up to no good. Therefore, they advised Pompey not to go. Regardless, Pompey still proceeded to board the boat that was sent to fetch him from his ship. The first person to thrust his sword into Pompey was Lucius Septimius, a former officer of Pompey. Then Achillas and the third assassin proceeded to finish Pompey off by stabbing the general with daggers.

The murder took place right in the view of Pompey’s ships. Stunned by the twist in events, the people on Pompey’s ship fled. They were not chased by the Egyptians.

Pompey was murdered at the age of 57, a day before his 58th birthday. His head was decapitated and his body left to be buried by one of his freedmen.

It’s said that the Egyptians presented the decapitated head of Pompey to Caesar, who flinched and asked the head to be taken away from his sight. And upon receiving the seal of his deceased ally-turned-foe, Caesar is said to have wept bitterly. After all, Pompey was Caesar’s former son-in-law by virtue of his marriage to Julia, Caesar’s daughter.

How Pompey got his epithet, Magnus (“Great”)

It’s been suggested that Pompey earned the cognomen Magnus (“the Great”) around 81 BC. This was in honor of the military achievements he chalked during Sulla’s Civil War. His mentor Sulla is said to have saluted him as Magnus (the Great) and then asked his men to call Pompey by that cognomen. The name also reflects Pompey’s admiration of Alexander the Great.

To his opponents, however, Pompey was known as the “Teenage butcher” (adulescentulus carnifex)due to his ruthlessness and the manner in which he decimated his enemies in Africa and Sicily.

Caesar’s Civil War

Caesar’s Civil War (49-44 BC), which is also known as the Great Roman Civil War, was caused by Pompey and Caesar’s refusal to disband their armies and lay down their weapons, as both feared the other. After successfully marching on Rome, Caesar caused Pompey to flee to Greece, where Pompey faced Caesar in so many battles, with the decisive one taking place in 48 BC. Pompey was defeated and fled to Egypt, where he was murdered by courtiers of Ptolemy XIII who did not want to anger Caesar.

After Pompey’s death, many allies of Pompey surrendered, including Marcus Junius and Brutus and Cicero. The few Pompeians that did not surrender, for example Cato the Younger and Metellus Scipio, were ultimately defeated by Caesar in 46 BC at the Battle of Thapsus in Africa. With the no Pompeian to stand against him, Caesar went ahead to be elected dictator for life.

More on Pompey the Great

Here are 7 other important facts about Pompey the Great:

- Pompey had a sister called Pompeia, who married Gaius Memmius and then Publius Cornelius Sulla. Publius was the nephew of renowned Roman politician-general Lucius Cornelius Sulla.

- After his father’s death in 87, Pompey was dragged to court for the an alleged theft that his father committed. Being the heir of his father, Pompey could perfectly be tried for the sins of his father, so to speak. Pompey defended himself brilliantly, catching the attention of the judge, who then gave his daughter’s hand in marriage to Pompey. The young military commander was also acquitted of the charge.

- Following the death of his mentor Sulla in 78 BC, he made sure that the former Dictator of Rome was given a state funeral and final honors befitting him and his accomplishments.

- During the Roman Empire era, both Caesar and Pompey were celebrated, with the former earning more of the praise. Imperial Rome erected a number of statues of Pompey, one was even placed in the forum of Augustus, Rome’s first Emperor and Caesar’s adopted son and heir. He was particularly admired by the nobles in Rome. This explains why his image featured on silver coins in 40 BC.

- In their time as consuls in 70 BC, Pompey and Crassus restored the tribunate, an office that was removed during Sulla’s reign.

- Pompey was consul on three occasions, in 70 BC; 55 BC; and 52 BC. He was elected sole consul of Rome in 52 BC.

- His effort, as well as the contributions he made in the First Triumvirate, is credited with laying the foundation upon which the republic turned to an empire.

FACT CHECK: At World History Edu, we strive for utmost accuracy and objectivity. But if you come across something that doesn’t look right, don’t hesitate to leave a comment below.