Jean-Jacques Rousseau – Beliefs, Famous Works & Major Accomplishments

Most known for his philosophical treatises Émile; or, On Education(1762), A Discourse on the Origins of Inequality (1755) and The Social Contract (1762), 18th century Swiss-French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau who stated that society loses its freedom when the social contract is fraudulent, which in turn sustains inequality and guarantees the rule of the rich. Many leaders of the French Revolution as well as the American Revolution drew tremendous inspiration from Rousseau’s works. The French political philosopher also inspired a good number of thinkers of the Romantic generation.

What else was Jean-Jacques Rousseau most known for? What were his beliefs and contribution to political philosophy? Below WHE delves into the life, political treatises and beliefs of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Fast Facts

Jean-Jacques Rousseau | In addition to having a big impact on the French Revolution, Rousseau’s philosophy and ideas have had influences on modern political, economic and social thought.

Born – June 28, 1712

Place of birth – Geneva, Switzerland

Died – July 2, 1778, France

Aged – 66

Parents – Isaac Rousseau and suzanne Bernard Rousseau

Wife – Thérèse Levasseur

Most famous works – “The Social Contract”, “A Discourse Upon the Origin and Foundation of the Inequality Among Mankind”, “Emile: or, On Education”, “Letter to Monsieur d’Alembert on the Theatre”, “Confessions”, “Julie; or, The New Eloise”

People he influenced – Immanuel Kant, Napoleon Bonaparte, Friedrich Nietzsche, Wolfgang von Goethe, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Maxmilien Robespierre

Birth and upbringing in Geneva, Switzerland

Jean-Jacques was born in the Swiss city of Geneva on June 28, 1712. His mother, Suzanne Bernard Rousseau, passed away of fever about a week after his birth. Therefore, he was raised by his father Isaac Rousseau, a Genevan watchmaker. It was from his father that he came to appreciate Geneva and its republican values. His father compared Geneva’s republican ideals to that of ancient Rome and even Sparta.

Time in Savoy

Rousseau was sent to live with his mother’s family after his father had a brush with the law, which forced Rousseau senior to flee Geneva.

His ten-year stay with his mother’s family was anything but pleasant. Rousseau, like his father, left Geneva. The 16-year-old headed to Sardinia, where he struggled to find his footing, living as a wanderer most of the time. He ultimately ended up in the province of Savoy (present day southeastern France).

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Madame D’épinay

Louise-Florence-Pétronille Tardieu d’Esclavelles, dame de la Live d’Épinay, byname Madame D’épinay (1726- 1783) established a congenial salon at her residence at La Chevrette, near Montmorency, which she allowed French leading members of the Philosophes to use as a meeting place. Those men were important thinkers of the period immediately before the French Revolution.| Image: Mme d’Épinay by Jean-Étienne Liotard, ca 1759 (Musée d’art et d’histoire, Geneva)

In Savoy, he was employed as a steward by a wealthy baroness, who also took him as her lover. Rousseau would use the baronne de Warens, who was about 14 years his senior, to climb up the social hierarchy in France. His hostess was herself a social climber who had run away to Savoy with almost all of her husband’s money.

With his lover’s help, he was able to acquire a very sound education that enhanced his intellectual prowess. He would develop into a fine thinker, scholar, and a lover of music. He also benefited tremendously from the fact that his hostess was a refined and intelligent woman. She was a well-respected figure in literary and philosophical circles in 18th-century France. She wrote a number of works herself; however, she is more famous for her friendships associations with three of the famous French writers and thinkers of her era, Baron Friedrich de Grimm, Denis Diderot, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Time in Paris

Around the age of 30, he moved to Paris, where he teamed up with a young and intelligent man of letters and philosopher called Denis Diderot (1713-1784). Rousseau and Diderot soon became leading figures of the philosophes, i.e. the circle of intellectuals and philosophers in Paris. Rousseau and members of the philosophes contributed to the French Encyclopédie, one of the major works of the Age of Enlightenment. Diderot served as the chief editor of the Encyclopédie.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s most famous opera – Le Devin du village

Rousseau’s original ideas were some of the reasons the Encyclopédie became an extremely important work of the age. He contributed tremendously to topics on music and economics for the Diderot’s Encyclopedie. He also wrote a number of operas. His opera, titled Le Devin du village (The Village Soothsayer), in 1752 is said to have received very positive comments from the French king Louis XV. The French king even offered Rousseau a pension, to which the philosopher turned down the honor.

Rousseau’s “illumination”

Although he had the opportunity to enhance his reputation and influence in the French court, having written operas that were loved by the French monarch, Rousseau chose a different path instead.

While on his journey to visit his friend Diderot, he claims to have been struck by a sudden clarity in the path that he had to take. In his autobiography Confessions, he described this realization as an “illumination”, which revealed to him the knowledge of how people descended into a life of vice and immorality as a result of modern progress. In other words, what society called progress was in actual sense a means of corrupting people.

Discourse on the Art and Sciences (1750)

Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750)

In the 1750 essay, which was titled A Discourse on the Science and the Arts (Discours sur les sciences et les arts), for the Academy of Dijon, Rousseau introduced his ideas and beliefs to the public. He states in the essay that society as we see it is not progressing; instead, it is retrogressing because the individual, who was born innocent, is continuously being corrupted by the society.

Sophistication leads to decay

Rousseau argues that human beings are good by nature; however they have been made corrupt by a society that calls itself civilized. Rousseau was not against civilization, far from it. Instead he was dismayed by the direction society had taken. He believed that the path on which civilization was on made humans corrupt. In other words, Rousseau describes how more sophistication leads to decay in the society.

People are naturally good

In terms of societal progress being the cause of corruption among people in a society, Rousseau’s ideas were not novel. Since the Middle Ages, The Catholic Church had held a similar notion. However, where Rousseau differed from the views of the Catholics at the time had to do with humans being naturally good.

By making human goodness the center of his philosophical reasoning, he set himself apart from the conservatives and radicals.

It’s been suggested that Rousseau’s core belief of seeing human purity and human goodness might have come from his mistress the baroness of Warens. Quote: Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Social Contract

Rousseau’s dispute with Jean-Philippe Rameau

Music was the first area that allowed him to make a name for himself. Therefore it came as no surprise that he got caught up in a dispute with a famous French composer by the name of Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764).

Initially, Rousseau and a number of the philosophes, including Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert (1717-1783), were admirers of Rameau. However, all that changed around the mid-1750s, when more and more Parisian philosophers and intellectuals began favoring Italian music over French music. Rousseau thus became a huge critic of French opera music, and by extension Jean-Philippe Rameau. The disagreement between the two men went beyond music to include philosophy.

Rameau, who was about 30 years Rousseau’s senior, did not expect Rousseau to put up a strong intellectual debate in both music and philosophy. The younger man heaped praises on Italian composers because their works prioritized melody over harmony. Rameau begged to differ, stating that harmony, balance, order, and rationality were everything when it came to music.

Rousseau’s contributions to music

Although not as experienced and well versed in musicology as Rameau, Rousseau’s arguments in favor of melody over harmony won a great number of intellectuals in Paris. He was of the view that music composers ought not to sacrifice their individual creative spirit in favor of rigidity and formal rules in music.

Rousseau’s support for freedom in music

Rousseau was very critical of French classical composers like Jean-Philippe Rameau for being so obsessed with making their works conform to rational rules and order. Rousseau noted that true music was not one that thrived to eliminate chaos using order. Instead, he argued that composers should remain very much in touch with their individuality and imaginative spirits that often are driven by spontaneity and vision.

A proponent of Romanticism

Rousseau promoted romanticism, which in some sense is the promotion of the primitive over the civilized; the young over the adult; and the passionate lover over the calmly loyal spouse.It is an intellectual orientation that does away with the precepts of calm, harmony, balance, idealization, rationality, harmony, order, and—so typical of Classicim and Neoclassicism and rationalism. Rousseau was able to convince French philosophes and music composer of the benefits that accrued when freedom is injected into music. Image: Statue of Rousseau on the Île Rousseau, Geneva, Switzerland

Rousseau’s argument was profound in the sense that it helped lay the foundational principle for what would later come to be known as Romanticism. He was thus one of the first thinkers in Europe to reject the precepts of balance, idealization, order and rationality that underpinned Classicism and rationalism. He praised Italian opera composers because of their pursuit of freedom in music.

In the end, Rousseau was able to convince more people to appreciate his ideas in music composition. This is the reason famous composers like the German Christoph Willibald Gluck and even Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart ended up crediting Rousseau as a major influence.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s political philosophies

In spite of the success of his opera Le Devin du village and his fame for his novel ideas in music composition, Rousseau did not pursue music composition any further. Instead he turned his full attention to philosophy. It was also around this time that he made a bold decision to pursue his ideas in moralism even further.

Rousseau’s explanation of the source of inequality

Using his proposition (i.e. human beings are naturally good) from his first philosophical work, Rousseau set out to work on his second discourse – Discourse on the Origin of Inequality. The goal of the discourse, which came out in 1755, was to provide a bit of answers as to why inequality existed in the society.

He pointed out that inequality was created natural and artificial inequality. The first kind of inequality arose when people have different skills, abilities and knowledge, which causes variation in endeavors and thereby produces different outcomes.

It was the second one – artificial inequality – that Rousseau was most concerned about. The philosopher argued in his 1755 Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (Discours sur l’origine de l’inegalité) that this kind of inequality emerged from the society and the manner in which it is governed.

He looked to nature to explain his ideas further. According to Rousseau, the first human beings lived a solitary life; they were also good, free and happy. However, that all changed when humans started forming societies. His arguments were in contrast to English philosopher Thomas Hobbes’s beliefs, which say that human beings’ lives at the start of creation were nasty and short.

Human vice is the outcome of organized societies

He goes on to state that immorality and vices emerged when societies got created by people. Before the formation of societies, humans lived in the state of nature. They were not vain and immoral. However, the moment the first hut went up and people started having neighbors, humans began to be consumed by jealousy, which in turn produced artificial inequality and vice.

Before the arrival of societies and civilization, what humans was an innocent self-love. They had no reason to compare the skills and accomplishments with other people. There wasn’t the need to be better than another person. That all changed when societies arrived – people living in neighborhoods began comparing themselves with one another; they became prideful and boastful; and the was the strong urge and need to be better than everyone in the society.

State of nature – a time when man was absolutely free and did not have the vice of greed, envy, pride and shame. Hobbes on the other hand, described the state of nature as anything but harsh and brutal.

The effect of property

According to Rousseau, the formation of societies created the need for some kind of framework for those properties to be kept safe. As a result laws were created and government was formed. To the Swiss-French philosopher, property causes inequality which is not seen when people lived in the state of nature. In the latter, no individual owned property and the world belonged to everyone. This assertion of Rousseau was much appreciated by the German philosopher and author of “Das Kapital” Karl Marx (1818-1883). Unlike Marx and his later followers, Rousseau did not author those discourses as a means to undo the past and return humanity to living in nature, where no one owned any property.

Civil society benefits only the rich and property-owning individuals

Having a civil society was crucial in order to keep the peace and to protect people’s property. According to Rousseau, everyone living a civilized benefited from the peace that was maintained; however, only a few property-owning individuals accrued the second benefit. The society safeguarded those people’s rights to property, while the poor are left without any property. By so doing civil society breeds inequality. The poor does not benefit from having laws and civilized societies, according to Rousseau. The philosopher goes on to say that the poor aren’t the only unhappy and unhealthy group in societies, the rich are also unhappy as they constantly compare themselves to one another thereby creating unsatisfied and discontented life.

Social Contract: Hobbes versus Rousseau

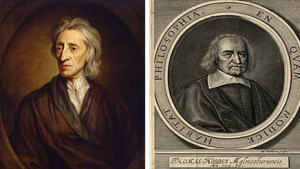

The leading political philosophers when it came to social contract were Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Swiss-French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Image: Renowned English philosophers John Locke (left) and Thomas Hobbes

In political philosophy, a social contract refers to an agreement – either hypothetical or actual – that exists between people in power and the ruled as to how they are to be ruled. Being a contract, the social contract defines the rights and responsibilities of every member of the society – i.e. the ruled and the rulers. In pre-civilized societies, this contract did not exist as people lived in a state of nature. The question that begs to be answered is: were those pre-civilized people happy or miserable? Swiss-French philosopher Rousseau believed that it was the former – people were simply happy in pre-civilized societies. Unlike the views of English philosopher and a big defender of materialism Thomas Hobbes, Rousseau kicked against materialism that came with civilized societies.

Hobbes interpreted the social contract to justify the unlimited power of the ruler/sovereign. In pre-civilized societies that had no social contract, Hobbes opined that life was very miserable, solitary and brutish. Hobbes had the tendency to highlight the disadvantages of the state of nature, describing it as one in a state of war. Therefore individuals had to come together to form a society where they agreed to place in the hands of the ruler their liberty and unlimited power provided the ruler could keep the peace and protect their property.

John Locke argued the soverign and the people agree that the state will have only a limited power and shall only be allowed to exercise this power to protect its citizens natural rights like liberty and justice. A state that fails to do this deserves to be toppled by the people.

Rousseau, on the other hand, sought to highlight the advantages of the state of nature. Rousseau’s Discours sur l’origine de l’inegalité argued that although humans were solitary in the state of nature, they were indeed happy, healthy and free. Upon the formation of societies, which he termed as “nascent societies”, people stated cohabiting in neighborhoods. That in turn resulted in the creation of vice, where people got consumed by destructive emotions of pride and jealousy. Furthermore, the laws and government, which arose in order to protect private property, in those societies further created inequality.

A fraudulent social contract

18th century Swiss-French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau opens his critically acclaimed work the Social Contract with a statement: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains”. By this the author meant that society loses its freedom when the social contract is fraudulent, which in turn sustains inequality and guarantees the rule of the rich. The poor in the society hardly benefit from a fraudulent social contract.

However, a society based on a genuine social contract is one that is underpinned by true liberty and republican values. In his work The Social Contract (1762), he came up with the term the “general will” (volonté générale). Societies with genuine social contract promote the general will of the people. In such societies, Rousseau argued that people give up their independence in order to attain a true kind of freedom and political liberty. People living under a genuine social contract will be bound by self-imposed law.

Volonté Générale (the “general will”)

What that meant was that the general will ranked above both individual rights and property rights. The state therefore had to make laws that safeguarded the general will as well ensure equality and liberty of its citizens. The people are obliged to rebel when the government begins to act contrary to the general will, Rousseau further stated.

Hate is the order of the day when people live outside the state of nature. Man is therefore by nature good, however, with time he gets corrupted by society and civilization

The inequality causes people to despise one another. Rather than the society aiming for a general will, i.e. common good, it gives rise to different and conflicting interests, which in turn fuels more hate in the society.

Rousseau reasoned that such social turmoil and social inequality are the result of people living outside the state of nature. He cited his birth city, Geneva, as an example of a society that had carefully balanced the demands of living in state of nature and outside the state of nature. He praised the republic of Geneva (under the Calvinist) of taking care to choose the right people to govern, i.e. people that aimed to protect the common interest of the republic.

Amour de soi versus Amour de propre

His belief in the natural goodness of man, led him to state that pre-civilized societies were guided by spontaneous pity and empathy for suffering of others. They had strong need for self-preservation, something Rousseau termed as “amour de soi” (“love of self”), and pity. Society enters a moral degeneracy as it becomes more and more civilized. People develop an unhealthy form of self-love he called “amour propre”, which is centered around jealousy, vanity, greed, and pride. This kind of love is destruction, Rousseau states.

Rousseau noted that as amour de soi turns into amour de propre, the empathy we have for one another diminishes. This is often caused by our strong need to not only learn from others, but to also compare ourselves to others. We tend to create our identity in reference to others, completely ignoring how we feel or the things that we want. Instead we are fixated on imitating others. Rousseau sees this ruinous competition as a big threat to our morality, as we lose sight of own sensations. The philosopher tags members of such societies as noble savages who aren’t psychological rich or interesting. Rousseau compares the modern decadence of our society to the innocence and morality of our ancestors.

Flaws in Rousseau’s arguments

In formulating his genuine social contract theory, Rousseau disregards the one important thing: every individual in a society has a single will. What it means is that a society is made up a collection of individuals with invidual wills. It is therefore inevitable that conflict will arise due to differences in wills. He tries to avoid this huge flaw by stating that the individual will have to make a vow to subjugate his/her will to the general will of the society. He proposes that natural rights of the individual be exchanged for civil rights. To Rousseau, the individual incurs no form of loss whatsoever, as civil rights trump natural rights, which he describes as vain and superficial.

Individuals that disobey the law (i.e. the general will) can be forced to obedience

Some critics of Rousseau argue that his ideas are stone throw from totalitarianism as the common will of the society is imposed on the individual. What happens when the individual refuses to give up his/her naturals rights for the “common good” of the society? Should that individual be ejected from the society? Or should the individual be forced into that exchange? Rousseau’s statement of “forcing a man to be free” sends shivers down the spine of many philosophers. In other words, Rousseau is completely fine with forcing minorities that have fallen into materialism to abandon their lifestyle in favor of the “general will” of the society.

True law versus actual law

In no part of his work the Social Contract does he support the notion of forcing the entire society to be free, that in itself goes against the collective will of the people. Rather he states that individuals that occasionally go contrary to the general will can be forced to obey the general will of the society. This view might sound alien to many modern liberals; however, our democratic institutions promote exactly what Rousseau’s proposes. Leaders are given the right the rule when they secure majority of the votes cast. The losers, by virtue of being members of the society, have to comply with the result of the elections.

The above point is related to the two kinds of laws – actual law and true law – that Rousseau talked about in his first discourse. States that are governed by actual laws often seek to maintain the prevailing state of affairs, even if that status quo is one based on a fraudulent social contract. However, states with true laws are ones that seek to protect the general will of the people. According to Rousseau, a true law is just in every sense since the people are the ones who make the law. The people can therefore be seen as some kind of collective sovereigns. Those self-imposed laws are better able to eliminate inequality since no group of people would impose upon themselves an unjust law.

The majority isn’t always right or intelligent

Considering how Rousseau’s whole argument supports creating a society where the general will of the people rules. And since that general will is dictated by the people – i.e. majority – what happens if the majority is not intelligent or capable enough to choose a just will? Rousseau, like Plato, thought about that same scenario. Both philosophers agreed that most people are simply stupid and naïve, and hence it’s is reasonably possible that the society will end up with laws that are moral but logically reprehensible.

Rousseau argues that such a dire situation can be avoided by having a strong and wise leader who will act as the lawgiver. That person will then make a constitution that is just in order to promote the general will of the people. The likes of ancient Babylonian king Hammurabi and ancient Greek statesman Solon come to mind; leaders of that caliber had to step in to keep the misinformed and stupid majority from plunging the society into turmoil. The leader could then educate the misinformed or less informed people to pursue things that are in accordance with the general will.

Rousseau even states that the leader has to claim divine power, then he/she should do so if that would help him/her get those just laws enforced.

The idea of the general will could also be an unrealistic aspiration as an individual by nature is selfish and would only vote for things that are in their self-interest.

Creating a homogeneous state

He argued that the individual has also sacrificed their true freedom after emerging from their pre-social state. The individual is plagued by vice and sin, something Rousseau refers to as “amour propre” (corrupted self-love). The civilized individual sacrifices his complete freedom for the power of the sovereign. To avoid this, the people should become the sovereign, Rousseau argues. By so doing, they would be able to be directly determine what is best for the entire population. The people should be the one with absolute power, Rousseau continued. They should be involved in creating laws that apply to everyone.

It must be noted that Rousseau is not arguing in favor of equality of property; instead, he promoted the equality of citizenship, which is the maximum freedom for all citizens. In such societies, the individual’s rights are protected by the community and the general will. He proposes that this system of governance could work in small states with direct democracy. Interest groups and factionalism would be banned in order to make the society homogeneous.

Niccolo Machiavelli and other philosophers that influenced Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a big admirer of Florentine political philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli as well as some of his views on maintaining a republic. | Portrait of Machiavelli by Santi di Tito

In addition to Plato, Plutarch, and Thomas Hobbes, French philosopher Rousseau also admired Niccolo Machiavelli. Rousseau appreciated many of the views that the Florentine political philosopher espoused in his discourse on how to build and maintain a republic. Similar to Machiavelli, Rousseau believed that the Church does not adequately prepare the citizens of the society to be of service to the general will of the people. He argued that making Christianity the religion of the republic would be catastrophic as the Church tends to pay too much attention on the invisible world. Hardly are virtues like patriotism and courage supported by the church in its relation with the state. He therefore proposed minimal use of ideas of the Church in the republic.

Letter to Monsieur d’Alembert on the Theatre (1758)

In his later career, Rousseau preferred living in Paris to Geneva. In 1754 after gaining his citizenship, he left Geneva for the second time. He liked the intellectually stimulating environment of the philosophes in Paris, France. His health began to deteriorate very fast due to a number of disputes he had with some members of the philosophes, including Jean Le Rond d’Alembert (1717-1783), who had wanted to set up a theatre in Geneva. He was also irritated by some colleagues of his who critized Geneva for straying away from Calvinist ideas. Rousseau’s 1758 work Lettre à d’Alembert sur les spectacles (Letter to Monsieur d’Alembert on the Theatre) was made to defend Geneva against those criticisms.

Émile; ou, de l’education (Emile; or, On Education)

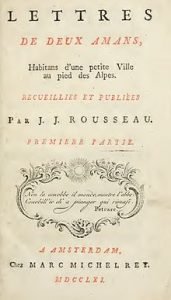

Rousseau’s Émile, published in 1762, was an outstanding treatise on education that talked about how children picked up vice and corrupt practices from external agents. The child, when born, is innocent, opined Rousseau, since vice is alien to a child’s nature. To counteract those vices, the parents or guardians ought to facilitate agents that diminish the child’s exposure to those vices. Image: Title page of Rousseau’s Emile

This work by Rousseau is talks about how parents should raise their children to prevent them from losing the natural goodness in them. Rousseau states that children are born naturally good, however, as they grow up, they get corrupted by the society. It was therefore the parents’ or guardian’s duty to prevent this corruption from happening. He suggests having a child-centered education, one that will also involve exposing the child to nature, forests and lakes. In the work, he also proposed breastfeeding as means to make children get in touch with their true natural self.

Rousseau’s Émile supports raising children in a manner that adequately prepares them for being very good republican citizens. Not only does the book appeal to the republican ethic of The Social Contract, it also supports the aristocratic ethic of The New Eloise.

In 1756, he moved from Paris to stay with his former lover Mme d’Épinay at her country house near Montmorency. But after a bitter quarrel with his hostess, he moved to cottage nearby. He was again on the move following the uproar that was caused by the publication of his treatise Émile; ou, de l’education (Emile; or, On Education).

Rousseau’s Émile was burned in Paris and an arrest warrant issued for Rousseau. With the help of his friend Maréchal de Luxembourg he was able to flee Paris. A year later, he renounced his Genevan citizenship.

La nouvelle Héloïse (The New Eloise) (1761)

La nouvelle Héloïse (The New Eloise), a novel that espouses the ideals of romanticism, did not receive the same censorship as Émile; ou, de l’education (Emile; or, On Education) and the Social Contract did. This was because, the novel, which was popular among educated women, focused on finding happiness in the home.

Following its release in the early 1760s, The New Eloise became popular among educated women. Its focus on family as well as finding happiness in the home made it very appealing to audiences at the time. The sentimental novel was the most widely read among his works in his lifetime.

It tells of a story of how a young middle-class man Saint-Preux falls in love with Julie, an upper-class pupil of his. However, due to their different classes marriage is impossible. Instead, Julie, being a dutiful daughter, marries the nobleman Wolmar who had been betrothed to her by her father. Saint-Preux then goes on a voyage around the world with an English aristocrat, from whom he learns a great deal of things. As for Julie, she learns to find happiness as a wife and mother. When Saint-Preux returns, he is recruited by Wolmar to tutor the children of Julie. The characters then go on to have very good lives after, living in harmony. However, in her latter days, Julie comes to the realization that her love for Saint-Preux was never extinguished.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s religious views

Rousseau believed in the existence of God. He also did not have any doubts about the immortality of the soul. As a matter of fact, he thrived towards the worship of God. He believed that he could feel God’s presence when he was in nature, in the mountains and forest and around things that were untouched by man.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s quotes

Time in England

After he was banished from the canton of Bern in Switzerland owing to a number of his publications, he migrated to England, where he was helped by the Scottish philosopher David Hume to get a pension from King George III. However, he became very paranoid and was driven to a point of insanity.

Unhappy in England, he returned to France, where he married his old lover and laundry maid Thérèse Levasseur in 1768.

Autobiographies by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Rousseau espoused a number of ideas, including ,maximum freedom for all citizens, direct democracy, and equality of citizenship. | 1766 portrait of Rousseau wearing an Armenian costume, Allan Ramsay

In his last decade, he devoted most of his time writing up a number of autobiographies, which received critical acclaim. One of such autobiographies was his Confessions (1781-88). Modeled on the work of St. Augustine’s Confessions, Rousseau’s autobiography was a huge success. He used it as a means to justify himself against his critics and adversaries.

Other autobiographies of Rousseau include Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques (1780; Rousseau, Judge of Jean-Jacques) and Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire (1782; Reveries of the Solitary Walker).

How did Jean-Jacques Rousseau die?

While taking refuge on the estates of the French noblemen, the Prince de Conti and the Marquis de Girardin, he took ill and died at Ermenonville. He was aged 66. The cause of his death was cerebral bleeding from an apoplectic stroke. He was buried on the Île des Peupliers.

Due to his popularity with many members of the Jacobin Club, he was interred as a French hero in the Panthéon in Paris on October 11, 1794. His remains are next to fellow French philosopher François-Marie Arouet, also known as Voltaire.

Other Jean-Jacques Rousseau facts

- Even though Rousseau did not gain much education, he was still able to rise and become one of the most influential thinkers of the 18th century.

- This Swiss-French philosopher’s ideas and thought had a huge impact on the intellectual thought of his era and all the philosophers that came after him. It’s been stated by some that Rousseau’s philosophies in some way brought to an end European Enlightenment (the “Age of Reason”).

- By pushed the boundaries of ethical and political thinking, he was able to produce works and treatises that contained many reforms that changed how we viewed the society.

- He wrote some of his most famous works while living at Montmorency. Example of those works includes Social Contract, la nouvelle Héloïse (The New Eloise), and Émile.

- In his mid-teens he fled Geneva to Savoy, where he converted from Protestantism to Catholicism. As a result, he had to relinquish his Genevan citizenship, which he later got back after his conversion back to Calvinism.

- Just before he started working on his political philosophies he repudiated his Catholicism and went back into the arms of the Protestant church.

- The theme in Rousseau’s The Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750) laments the loss of people’s liberty due to living outside the state of nature. On the other hand, The Social Contract (1762) explains how societies can ameliorate the problems that come from losing their liberties.

Other notable works by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau produced a good number of works that were credited with the cultural transformation of his era. Those works covered a wide array of areas, including ethics, literature, political philosophy, and democracy. Example of his other notable works are:

- Narcissus, or The Self-Admirer: A Comedy (1752)

- Letters Written from the Mountain (1764)

- The Cunning-Man ()

- The Reveries of a Solitary Walker (1782)

- Letters on the Elements of Botany (1785)

Top 5 Quotes by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s quotes from works such as Émile and Confessions

Conclusion

Most people are likely to say that humanity’s advances in sciences and the arts have in so many ways contributed to making the world a better place. For starters, we have come a long way from the era of slavery, subjugation of ethnic, religious and sexual minorities, and the denial of women’s rights and freedom. In other words, the world was getting better because we continuously strive to purify our morals. Swiss-French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau begged to differ. The 18th century political thinker believed that civilization and organized society haven’t improved people’s lives. Building of the works of philosophers like John Locke and Thomas Hobbes, Rousseau argued that the civilization has indeed corrupted the morality of human beings, who were once good in their state of nature.

Quote by Jean-Jacques Rousseau